Casement Park is tightly bounded on three sides by residential accommodation, with only limited exiting otherwise than at the Andersonstown Road frontage. However, it is accepted by all parties that an emergency evacuation scenario in which the Andersonstown Road exits are all closed is reasonably foreseeable. That scenario poses tremendous difficulties for the proposed new stadium in meeting the requirements for safe evacuation of spectators, particularly from a full capacity event with over 34,500 attendees.

The emergency evacuation solution proposed by the GAA in that scenario is based on routing spectators from the stadium to the Stockmans Lane Roundabout, underneath the M1 motorway. That proposed solution defies logic. It poses a serious risk to public safety.

The Stockmans Lane Roundabout Scenario

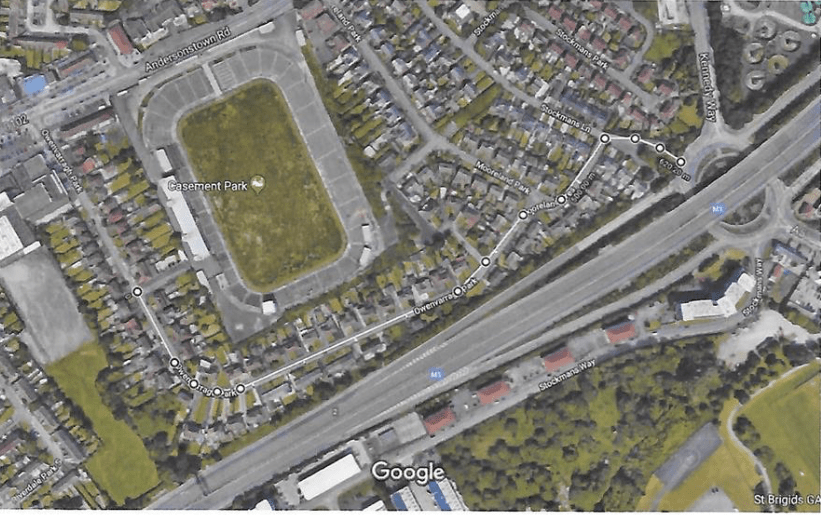

In a scenario where the stadium needs to be evacuated and the Andersonstown Road exits are not available, the contingency plan for a full capacity crowd (34,578) would route spectators from the stadium to some unspecified place of safety via the Stockmans Lane Roundabout. The route from the Owenvarragh Park exit to the Stockmans Lane Roundabout is illustrated below:

Owenvarragh Park to Stockmans Lane Roundabout – 620 metres

Imagery ©2018 Google, Map data ©2018 Google

The final portion of the evacuation route – 45 metres long – narrows to a footpath only. Widening of that footpath is constrained by the presence of an electricity pylon.

Footpath leading to Stockmans Lane Roundabout pedestrian exit, from Stockmans Lane

The evacuation route leads to a single pedestrian exit from Stockmans Lane that is just 1.9 metres in width and protected from the motorway roundabout by a steel barrier measuring close to 30 metres.

Pedestrian exit to Stockmans Lane Roundabout, from Stockmans Lane: Width = 1.9 metres

Unacceptable Risks to Public Safety

The proposed use of the Stockmans Lane Roundabout poses unacceptable risks to public safety.

First, each of the evacuation routes to the Stockmans Lane Roundabout would entail a narrowing of escape routes. That is contrary to the principle of simultaneous evacuation and the concept of continuous exiting. The crowd pressure risks to public safety would be most acute at the exit from Stockmans Lane to the Roundabout. There, the escape route narrows to a width of 1.9 metres. Consequently, there would be severe crowd build-up at the Stockmans Lane Roundabout exit. The evacuating crowd would effectively have to be ‘held’ within the surrounding streets (the Mooreland and Owenvarragh ‘horseshoe’ and the Stockmans Lane area) over that period of time, leading to a risk of crushing. That is entirely contrary to the concept of a free-flowing exiting system.

Second, the Stockmans Lane Roundabout scenario provides ample evidence that there is no design solution to safely accommodate large crowds at a redeveloped Casement Park, whether for sports or concert events. Rather, it is proposed to manage safety issues on a contingency basis, with heavy reliance on crowd control measures (thus far, undisclosed). That presents its own problems of coordination and, ultimately, capacity to respond to unanticipated circumstances.

Those risks were not addressed by the Department for Infrastructure (DfI) in the assessment of the Casement Park planning application. Effectively, the planning authorities deferred substantive consideration of safety issues to the Safety of Sports Grounds regulations. However, as the proposed evacuation route is external to the proposed stadium, the risks would not be effectively regulated under the Safety of Sports Grounds Order, which pertains solely to the curtilage of the relevant sports stadium.

The potential risks to public safety from the proposed use of the Stockmans Lane Roundabout are well illustrated by the tragic Love Parade disaster which occurred on 24 July 2010, in Duisberg, Germany, when 21 people lost their lives. The Love Parade disaster was not the result of any one factor. Rather, it was the result of a combination of factors (see Box A below). The combination of factors that precipitated the Love Parade disaster are now ominously apparent in the disjointed approach to emergency evacuation from the proposed Casement Park redevelopment.

More Questions than Answers

As the possibility of an emergency evacuation in a scenario where the Andersonstown Road exits are not available is reasonably foreseeable, the contingency plans for dealing with that possibility would need to be in place on each and every occasion of a major (or medium) event at a redeveloped Casement Park. That would entail significant deployment of resources by the police, fire and ambulance services. The direct monetary costs of those resources have not, to date, been taken into account in assessing the costs of operating the proposed new stadium. Nor have the opportunity costs. If the police are busy implementing the proposed evacuation contingency plan, they are not available for other policing duties, such as preventing crime. Similarly, ambulances on standby at Casement Park are not available to respond to emergency calls at other locations.

The proposed solution also raises a host of questions around traffic management and pedestrian safety during any major or medium-sized event at the proposed new stadium. For example:

- Would the Stockmans Road Roundabout require to be closed off completely to non-spectators while an event is in progress, to be prepared for the ‘reasonably foreseeable’ evacuation? If so, how would displacement of non-spectator traffic be managed?

- Would traffic management arrangements need to be implemented on the stretch of the M1 which passes over the Stockmans Lane Roundabout? Again, how would displacement of non-spectator traffic be managed?

- Would the streets surrounding the stadium be subject to a lockdown, to keep the roads clear in the event of an emergency evacuation to the Stockmans Lane Roundabout? Would residents be asked to park elsewhere during events?

- Even when the crowd has reached the Stockmans Lane Roundabout, where would they go? The Boucher Playing Fields? Somewhere else? In any event, the crowd would still be on the public highway for some time after exiting Stockmans Lane.

- What infrastructure works would be required to modify the Roundabout for use as an emergency evacuation route? Undoubtedly, the Roundabout has not been designed for such a purpose.

All of the above considerations point to a much lower capacity for any redevelopment of the Casement Park stadium. Certainly, no more than 15,000.

Note: A ‘reasonably foreseeable’ possibility

In April 2015, serious concerns were raised around safe evacuation from the proposed Casement Park in the event of an emergency. Those concerns were aired through expert evidence to a Committee of the Northern Ireland Assembly. Subsequently, the then-Minister commissioned a Project Assessment Review (PAR) of the stadium plans[1]. The PAR was undertaken by a team led by the UK Cabinet Office.

The PAR report was submitted in August 2015[2]. Based on its consultations with the Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI), the review team accepted as “reasonably foreseeable” a scenario in which the Andersonstown Road exits are all closed[3]:

We agree that needing to scenario plan for the closure of all Andersonstown Road exits is onerous, however we heard persuasive evidence from PSNI representatives that a scenario that closes all of the Andersonstown Road exits and at the same time requires an evacuation of the stadium is reasonably foreseeable. … PSNI representatives shared with us the prescribed length of cordon they would need to put around various types of suspect device and we are satisfied that this meant there could be scenarios where a length of Andersonstown Road wider than the stadium entrancing/exiting area on Andersonstown Road might need to be closed. (Emphases added).

| Box A The Love Parade disaster, Duisberg, Germany |

| The Love Parade disaster cost 21 lives in a crush at a techno festival held in Duisberg, Germany, on 24 July 2010. The festival site covered approximately 100,000 square meters, located in a former freight station of the city. To gain access to the festival, concert goers were funnelled through a single 400 metre long tunnel. The city of Duisberg approved the event with a condition to restrict the number of concurrent visitors to 250,000. For various reasons, which are discussed in Helbing and Mukerji (2012), on the day of the festival, the tunnel became over-crowded. In the resultant crush, 21 people, aged between 17 and 38 years, lost their lives. A further 652 people were injured. According to Helbing and Mukerji, the Love Parade disaster was not the result of a single mistake. Rather, it resulted from the interaction of several contributing factors: “… the Love Parade incident shows the typical features of crowd disasters, such as the existence of bottlenecks (and therefore the accumulation of large numbers of people), organizational problems, communication failures, problematic decisions, coordination problems, and the occurrence of crowd turbulence as a result of high crowd densities”. Nonetheless, the main proximate factor identified by Helbing and Mukerji was the crowd build-up at the entrance to the tunnel, due to the imbalance between the rate at which concert-goers were arriving at the entrance compared to the rate at which they were exiting the tunnel to enter the venue: “The main cause of the disaster was simply the great density of visitors at the entrance to the festival area. If more and more people head to one place, they come closer to others and, at some point, so close that their bodies touch each other. All movements – not only intentional pushing, but also unintentional movements – are then transmitted through the crowd. If someone stumbles, this can lead to a domino effect, where many people fall on top of others. Those ending up below a pile of people are often unable to get enough air.” Hebling and Mukerji make a number of other pertinent observations, as follows: “The capacity of the area of the mass event already implied various problems, which the organizational concept wanted to overcome by crowd control. However, the delayed start of the event and the unexpected obstruction of the inflow to the festival area from the ramp (i.e. two factors which were probably not anticipated) caused queues that were difficult (or impossible) to manage”. “In advance of the event, concerns were raised that the standard safety requirements would not be met. It is conceivable that these concerns were not fully considered due to a desire to approve the event.” “To overcome the concerns, an expert opinion was requested from a prominent crowd researcher. The [research] report argued that the festival area could be sufficiently well evacuated in an emergency situation”. Unfortunately, that did not prove to be the case and Hebling and Mukarji note that, while “computer simulations can often help to identify crowded areas, … they are not sufficient to reveal all kinds of organizational challenges”. |

| Reference: Helbing, D., and Mukerji, P., 2012. “Crowd disasters as systemic failures: Analysis of the Love Parade disaster”. EPJ Data Science, 1:7. https://epjdatascience.springeropen.com/articles/10.1140/epjds7. |

[1] BBC, Casement Park: Sports Minister calls for stadium review after committee claims, 30 April 2015, at https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-northern-ireland-32530978.

[2] DCAL Stadia Programme– Project Assessment Review, August 2015. Available at https://www.communities-ni.gov.uk/publications/dcal-stadium-programme-project-assessment-review-report.

[3] Ibid, page 26.

Leave a comment